Dissertation: Niklas Luhmann: A theoretical illustration of his definition

of differentiation

Copyright by

MICHAEL G. TERPSTRA

1997

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

PROLOGUE

CHAPTER ONE:

STATEMENT OF PURPOSE ---------------------------------------------------

10

CHAPTER TWO:

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE:

NIKLAS LUHMANN AS AN EXTREME POSTMODERNIST ------------

13

CHAPTER THREE:

THEORETICAL CONSIDERATION WHEN EXAMINING NIKLAS

LUHMANN’S THEORY OF DIFFERENTIATION -------------------------

28

Background And Development For The Subject-Free Concept -----

29

Double contingency ------------------------------------------------------

37

Interpersonal Interpenetration ------------------------------------------

40

Self-Reference ------------------------------------------------------------

41

Cartoon Strip

System And Environment -----------------------------------------------

47

Elemental Constructs ------------------------------------------

47

Essential Features -----------------------------------------------

48

CHAPTER FOUR:

ILLNESS AS A SYSTEM OF INTERPENETRATION :--------------------

53

ILLUSTRATION THROUGH A CASE STUDY

Complexity ----------------------------------------------------------------

57

Double Contingency -----------------------------------------------------

58

Autopoiesis ---------------------------------------------------------------

60

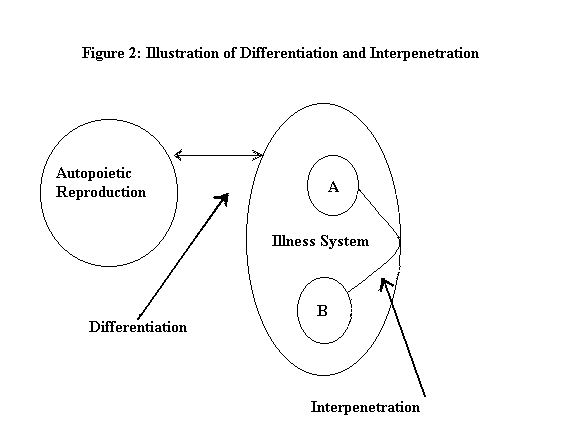

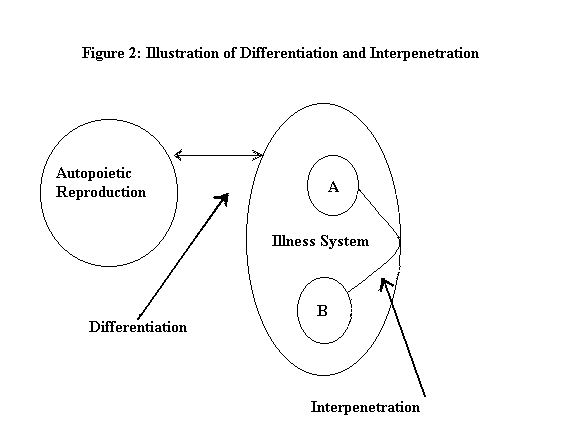

Illustration of differentiation and interpenetration

Case Study Illustration --------------------------------------------------

63

CHAPTER FIVE:

CREATIVE MISREADINGS ---------------------------------------------------

68

Illustration of Two Types of Misreadings: -----------------------------

70

Fragmenting Misreadings ---------------------------------------

70

Compromising Misreadings -------------------------------------

71

CHAPTER SIX:

POSTSCRIPT:

PUTTING THE PIECES TOGETHER ------------------------------------------

75

REFERENCES --------------------------------------------------------------------

79

APPENDIX A:

SEGMENT OF CASE STUDY DIALOGUE (TEXT) ------------------------

85

APPENDIX B

DETAILED ANALYSIS OF CASE STUDY SEGMENT --------------------

96

Go to Table of Contents

Documentation of correction since originally published in March 1997

June 30th, 1998 errata #1 page 70 , errata #2 page 74

Chapter 5 has been expanded and revised as, The Illusion of Theoretical Purity.

Please e-mail comments to Mike at: mgterpstra@cryogen.com

Visit my web site: Mike's Personal

Website

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

"No man knows fully what has shaped his own thinking."

Robert K. Merton

If there is one person I would single out in acknowledging contributions

to my work, it is my wife, MaryAnn Stirling Terpstra. This endeavor

has had the generous financial and emotional support of my parents, Dr. Chester

Terpstra and Dr. Margery Williams Terpstra. My son, Brooke Terpstra,

donated time and artistic talent to create my cartoon. My daughter,

Heather Martinez, made sure that my grandsons kept me grounded in real life.

The patient mentoring by Jeremy Shapiro provided me with the academic

climate to stimulate my imagination in pursuit of this theoretical dissertation.

Dr. Marlene von Friederichs-Fitzwater, friend and colleague, gave generously

of her time and resources. She was a valuable sounding board in many

brainstorming sessions. Roger Davis, a Fielding student, provided

encouragement and helped me keep a balanced perspective. Dr. Robert

Holub, Chair of the German Department, University of California at Berkeley,

provided initial validation of the value of my ideas. Finally, I am

deeply indebted to Professor Niklas Luhmann for the time he spent responding

to both my written and oral queries.

Go to Table of Contents

PROLOGUE

The prologue provides the reader of my dissertation with an outline of the

process involved in the development of the ideas. This preface will

identify problems encountered while preparing a theoretical dissertation.

Central focus is on my role as the interpreter of concepts and social principles.

At the beginning of this dissertation process, I intended to examine

methods for analyzing chaotic and interactive patterning in conversation.

The setting for this examination was the clinical encounter. I didn’t

accept standard explanations for what I saw in the dialogues of these encounters.

Simple answers for complex social problems such as Acquired Immuno-Deficiency

Syndrome (AIDS) led me to conclude that social analysis required the study

of complexity.

Interpreting the dialogue between patient and physician expanded beyond

the range of the analysis of conversation to the interpretation of

concepts and social principles. Questions about the interaction between

language and social dynamics complicated the analysis of the clinical encounter.

I explored the nature of illness and the effect this event had on the patient.

Interpretation has its origins in the study of the "subject."

Analysis shifted from concentration on the linguistic structure of the clinical

dialogue between patient and physician to a philosophical exploration of

the "subject."

The development of my dissertation topic began with a request

to examine the feasibility of using a particular analytical method (Markov

Chains). My task explored whether Markov Chains could further explain

the results of a published study. This study on physician-patient encounters

pointed to a lack of physician comprehension originating with a contrast

between what the physician heard the patient say and how he or she responded

(von Friederichs-Fitzwater, Callahan, Flynn, & Williams,

1991). The next decision was to choose the type of analysis for

the structure of conversation. My research background and methodological

approach has an ethnoscientific (Tesch, 1990,

p. 25) grounding. Therefore, my focus was on language, and

began with the structural analysis of language. My sociological perspective

was heavily influenced by Talcott Parsons' "action elements" (Parsons, 1951). The conversational dyad (physician

and patient conversing during a clinical encounter) meant that I would explore

a process of interactive patterning (Parsons, 1951,

p. 24).

Theoretically, the Markov Chain seemed like a plausible explanation

of interactive patterning. However, the study of physician/patient

encounters did not meet the requirements for a Markov process analysis.

Early 1970s probability studies using Markov Chains focused on syntax in

order to predict language utterances, and failed to show that this method

was appropriate for language (Rubenstein, 1973).

Although I did not apply the Markov process, I explored the appropriateness

of the stochastic process, of which the Markov Chain is an example.

My sociological background was consistent with a stochastic approach

which "views dyadic conversation as a process (actions that are connected

over time), comprising relational (between two people), structural (connected

actions that are subject to differing degrees of constraint), and informational

(the type of information being communicated) properties" (Thomas, Roger, & Bull, 1983, p. 177).

In the study of physician-patient clinical visits (von Friederichs-Fitzwater,

Callahan, Flynn, & Williams, 1991), I noticed a disproportionate number

of passive sentences used by AIDS patients during these meetings. In an attempt

to understand this particular anomaly, I developed a structural equation

model to identify any latent (hidden) variables in the transcribed dialogues.

This approach (Loehlin, 1987) allowed me to search

for nonlinear relationships in the grammatical structure of the clinical

encounters. The computer model used in this study was LISREL (Joreskog, Sorbom, 1993) because of LISREL's ability

to compute a confirmatory factor analysis. "The model is based on a priori

information about the data structure in the form of a specified theory or

hypothesis,..." (Joreskog, & Sorbom, 1993, p.

21).

Prior to the LISREL computations, a study of linguistics and the grammatical

explanations surrounding the passive voice was conducted. My conclusions

confirmed a "non-immediacy" or distancing (Wiener & Mehrabian,

1968) factor found in grammar. My study indicated that the passive voice

might be an indicator for nonimmediacy in conversations between AIDS patients

and their physicians. I then turned my attention to the linguistic and conversational

structure surrounding the AIDS patients' conversations. My next query

explored the relationship I found between the use of the personal pronoun

"I" and the "agent" (logical subject) of passive voice. I wanted to

know if nonimmediacy and passive voice were related concepts. My interest

was in following the development of information within the context of the

patient's conversation. I questioned whether nonimmediacy and

passive voice share meaning by reinforcing the relationship between speaker

and subject matter.

I wanted to know what this "distancing factor" meant because, from the

contexts of the dialogues, it did not appear that the interpretation was

consistent with the established definition of distancing. The traditional

meaning assumes that the patient is distancing himself from the other speaker

or from the topic of discussion.

The route I took to understand this interpretation problem led me to

an extensive exploration of linguistic theory. Traditional grammar,

using concepts of subject, verb, and object, requires certain presuppositions.

For example, Noam Chomsky (1957) developed

a scheme of transformational grammar that looked for major change in the

function of the subject, verb, and object. This approach led theorists

to seek universal characteristics in language. Searching for universals

is a cumbersome process. One becomes so overwhelmed with language

data, variations, and exceptions that perspective is lost.

In order to understand the subject in my case, the AIDS patient I had

to restrict my conclusions to rules of grammar: in this case, the distancing

or nonimmediacy characteristics of the passive verb. If I took the

entire dialogue into consideration in the light of traditional interpretation,

the required conclusion was not consistent with the evidence. In other

words, the patient, according to a transformational interpretation, should

have exhibited retreating behavior; but, in the context of the encounter

with his physician, it was obvious that he was confronting his problems.

It was at this point that I began my exploration of the interaction

between language and social dynamics. During this study another problem

emerged. Now my concentration turned to the area of the subject.

The problem became one of how to understand the identity of the person.

The problem became a question of knowing the patient rather than making assumptions

about what the patient was saying based on grammatical rules.

My linguistic studies now turned to the grammatic and linguistic theory

of cognitive grammar (Langacker, 1990, 1991).

Grammatical structure no longer provided me with the means for understanding

the language of the patient. Cognitive grammar discarded

this notion of grammatical structure (syntax) and replaced examining

the relations between subject and object with a semantic and symbolic basis.

My theoretical sociological interest settled more and more on Niklas

Luhmann's theory of differentiation. My initial interest and curiosity

about differentiation is found in the following personal account.

Before I started my current studies, I spent some time developing and assisting

in the implementation of a decentralized nursing management system at a Northern

California hospital. During this time, I pursued an interest in small

group process and worked extensively to set up employee work unit councils.

These groups of unit-based employee councils fed into several task- and administrative-specific

centralized committees. It was not until May 3, 1988, when I met with

Virginia Cleland, a nursing scholar at the University of California, San Francisco

(UCSF), that we identified that the governing councils served a differentiative

function, while the central committees were integrative. The individual

governing councils were a work unit participative decision-making body.

Their function was to identify problems in their workplace and to develop

solutions. The central committees consisted of representatives from

each of the governing councils, administration, and management. The central

committees developed policy based on the actions of the councils and advice

from management and administration. The governing councils functioned

in a differentiative mode. Differentiation, in this instance, cannot

be understood in the same vein as I later use the term in the dissertation.

Differentiation, here, I associate with delineating an individual’s roles

and responsibilities in which effectiveness comes from gathering information

and providing ideas for solutions to problems. The central committees provided

the organization with another function. That function integrated the

diverse input and unique characteristics of the governing councils into a

functioning whole. This was my introduction to differentiation and integration

as organizational functions worth further investigation.

Returning to the sociological perspective of Talcott Parsons' action

theory (Parsons, 1951), I addressed the relationship

between individuals and social systems. Parsons developed seminal

work in sociology, inspiring a variety of further social theorizing.

Niklas Luhmann was one of those theorists who revitalized the structuralist-functionalist

social theory of Parsons. Although theorists apply Parsons' "action"

concepts to their foundations for theoretical development, the directions

those theories take are sometimes very different. In his book, "Moral

Consciousness and Communicative Action" (1990),

Jurgen Habermas extends his communicative action theory, combined with Kohlberg's

theory (1973, 1984) of moral development, to

find support for a communicative ethic. James S. Coleman (1990) developed a different social theory than Luhmann.

I think the reason for this difference is primarily due to the concentration

Coleman placed on the structural nature of Parsons, while Luhmann took up

the functionalist position. Habermas is more consistent with Parsons’

structuralism as he developed his interactive approach to communication.

It is at this juncture that my previous work with stochastic process

and interest in differentiation led me to further explore Luhmann's theory.

In order to retain my focus on the conversation between the AIDS patients

and their physicians, I was particularly interested in using Luhmann's concept

of self-reference (1990a). The concept

of self-reference provided no insight into my patient/physician encounter

until I was willing to reexamine the "subject" philosophically. Luhmann

defined self-reference: "designates every operation that refers to something

beyond itself and through this back to itself" (Luhmann, 1986a, p. 145).

Eventually, Luhmann’s concept of a subject-free systems approach to the analysis

of social processes allowed me to transfer my thought processes from nonimmediacy

to self-reference.

Without going into the specifics of these investigations, my study of

the debates between Gadamer and Habermas, on one hand, and Luhmann and Habermas,

on the other, helped me to distill the essentials for the focus of my theoretical

dissertation. My argument is that, in the postmodern world, a systems

approach must take advantage of the present information age in order to meet

the requirements for effectively utilizing that information through the self-referencing

process. Luhmann's system of self-reference is the theoretical tool

needed to meet the needs of the postmodern world. As a proponent of

Luhmann’s theory as a solution to the information overload, I suggest that

we can no longer deal with the problem in the same old way, with information

as property and with subject/object as the center of an analytical system.

Theorists must step outside the current, comfortable mode and take a look

at a system without subject and with the fluid capacity to handle massive

amounts of information. The amount of information available today is unmatched

in any prior century. The means to store and manipulate it has never

been more accessible and technologically advanced. Making that knowledge useful

is the challenge.

Niklas Luhmann, through a second-order cybernetic systems approach,

insisted that society’s problems be viewed from the perspective of the difference

between the system and its environment. In other words, "second order cybernetic"

means that we, the observer, are part of the system of observation. Access

to information and its utilization as knowledge gives us the key to find that

difference.

Go to Table of Contents

CHAPTER ONE

STATEMENT OF PURPOSE

My process began with an examination of methods for the analysis of chaotic

and interactive patterning in conversation, paired with Parsons' notion of

"action elements," the nonimmediacy of passive voice, and inquiry into the

nature of the subject. I discovered that the concept of the subject

leads to dead ends when applied to methods of analysis. The subject

defines the focus of thought, speech, or written material while reinforcing

the belief that one is dealing with things as a manageable reference point.

The solution was not in the avoidance of the traps of subjectivity but rather

in discarding the subject altogether. The application of a subject-free concept

is set in the description of antagonistic beliefs present in the complex social

domain. Today’s world is a very complex environment, where social systems

need to reflect the complexity. Modern technology continues to create

a plethora of tangled information sources. As people choose a means

to deal with the overload of information, frequently the choices are diametrically

opposed to one another.

In the attempt to deal with the difficulties contributing to our current

state of being, solutions come from the observation of others. Knowledge

of self is available to a person only through outside observations.

That knowledge is communicated by the social system in which one is currently

involved. Luhmann rejected the approach to self-knowledge which presupposes

an actor in the sense of subject. In other words, solutions to one’s

own problems are not found through introspection. The implication for the

type of connection Luhmann proposed involves rethinking the way in which

we know ourselves. Luhmann not only challenged the subject,

he illuminated it.

Luhmann saw the connection with the world through insistence on the

fundamental limitations of all observations. It is impossible for anyone

to have any direct knowledge of self. One has blind spots in description

of self. People have access to self-knowledge through others’ descriptions.

This reliance on outside descriptions is liberating and does not separate

or alienate us from our world. The concept of the subject has historical

value, and its development contributes to the richness of social discourse.

Luhmann acknowledged the fact that the subject exists, but insisted that

the individual cannot adequately describe complex modern society without

the communication of social systems.

Information is dormant until it is communicated. Communication

cannot be directly observed. In order to demonstrate something we

cannot observe, we need some type of marker. Language, therefore, is

the evidence of the process of differentiation which demonstrates the difference

between a system and its enviroment, that is, communication. This is

in the context of a subject-free concept where the individual (subject) does

not assume the role of "actor."

Self-reference, in the traditional subject terminology,

refers to the individual as the object of reference. In Luhmann’s terminology,

self-reference refers to social systems and the function of self-referral.

When there is no object of reference - - only a process of differentiation

- - the only evidence that differentiation has occurred is language.

The purpose of this dissertation is to clarify Luhmann's subject-free

concept of action in a way that shows its appropriateness as a solution

to the problem of the subject. The approach taken is to theoretically

illustrate Luhmann’s theory of differentiation by: 1) setting Luhmann's

presence in the context of the postmodernist discussion, 2) exploring the

foundation for a subject-free concept and the rationale for the system-and-environment

scheme of differentiation, 3) illustrating Luhmann's definition of differentiation

with a case study of a clinical encounter, and 4) wrestling with the feasibility

that Luhmann's theory of a subject-free concept of action can transfer to

an analytical model.

Go to Table of Contents

CHAPTER TWO

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE:

NIKLAS LUHMANN AS AN EXTREME POSTMODERNIST

What is an "extreme post modernist?" For some, Niklas Luhmann fits

this description (Kellner & Best, 1991, p. 284).

Postmodernism is a term used to describe current thinking that challenges

the avant-garde positions of modernists. The perspective on postmodernity

with which I start comes from a quote: "One way of understanding the so-called

postmodernism debate is to see it as a debate about what modernity is, and

about those parts of it we want to perpetuate and those we want to discard"

(Kelley, 1990, p. 76).

Kellner’s and Best's description of postmodernism helps to position

Luhmann's work in the context of current theoretical development. The

section by Best and Kellner, entitled: "Postmodern Politics: Subjectivity,

Discourse, and Aestheticism," serves as my point of departure (Kellner & Best, 1991, pp. 283-294).

Here, postmodernism is defined by its failures. If the criticisms originate

from the assumption that postmodernism is looking for solutions to problems

of emancipation, then the authors are correct in their analysis of postmodernism.

On the other hand, if emancipation is no longer the driving force behind

the search for solutions, then recounting the failures is no longer relevant.

Formerly, the source of knowledge (information) was in the control

of the expert. If wielding that knowledge created oppression,

emancipation was necessary to free the individual from that oppression.

Boyle (1996) told us that we are possibly entering

a period of information overload. This implies that the fears of the postmodernists

may bear fruit, that we have inadequately prepared ourselves for this potential

disaster. The solution begins with information defined as an event

rather than a commodity. As a proponent of Luhmann’s theory as a solution

to the information overload, I suggest that we can no longer deal with the

problem in the same old way, with information as property and with subject/object

as the center of an analytical system. Theorists must step outside the current,

comfortable mode and take a look at a system without subject, and with the

fluid capacity to handle massive amounts of information.

A continued discussion of Best’s and Kellner's enumeration of

postmodernism's failures will further illustrate the definition of differentiation.

The definition of postmodernism includes elements pertinent to the

debate about the information age. I believe that Luhmann is addressing

the information age and the complex issues surrounding it.

The stimulus for this conclusion originates with Luhmann's idea

that communication requires the synthesis of three selections: information,

utterances (Mitteilung) and a need to "understand it all" (Luhmann, 1990a, p. 3). In order for communication

to be a function of social systems, Luhmann defined information as an event.

Once information is conceptualized as an event, then the process of synthesizing

information, utterances, and understanding becomes feasible. When

social systems function in their communicative capacity, then the complexities

of intersubjective interactions are eliminated. Luhmann’s strategy

is to use an abstracted systems model in which the basic unit is not the

social role, as with Parsons, but rather the communicative function of social

systems.

The problems of the information age include addressing issues faced

when accessing an overwhelming amount of information. The problem affects

the determination of the validity and usefulness of the superabundance of

information. Luhmann's systems theory connects the person to the information

by giving control. Control is in our hands because we are part of an

all-inclusive approach to the defining of reality. Information is not a commodity,

but is included in the synthesis of events that contributes to the communication

of the system.

The enumeration of the perceived failures of postmodernism sets the

agenda. The postmodern agenda includes the exploration of the theory

of differentiation, especially the distinction Luhmann made between system

and environment (1982, p. 230).

The critics of postmodernism identify an inadequate notion of subjectivity

which puts the subject (actor) in an isolated position, one without meaning.

Luhmann contributed to this postmodern debate on subjectivity with his concept

of a subject-free approach to the relationship between antagonistic beliefs

in the social domain. Although I argue for Luhmann's position on the

"subject-free" concept, Luhmann recognized modern philosophy's need for a

reinvigorated concept of the subject. If one requires the subject to

understand reality, then Luhmann expanded its foundation to be inclusive

of "all processes and systems within which 'meaning' plays an essential role" (Luhmann, 1982, p. 325). Luhmann

guarded against the use of the term "subject" because, historically, it

has acquired an individual personal referencing connotation. The desire

to avoid the confusion between action and its presupposed actor requires the

conscious effort to view both action and actor as constructs of the observer.

Therefore, any reference to self-perception must be seen as the observer’s

invention.

The foundational accomplishment of postmodernism is its recognition

that subjectivity needs reconstruction. Several authors recognized

this contribution in a variety of expressions (Knodt, 1994;

Jameson, 1991; Kellner &

Best, 1991). Knodt pointed out that "the binary logic of classical

ontology is exhausted" (1994, p. 93). This

means that the logic which maintains a separation between the subject and

object no longer holds. In a discussion of literary style, Jameson demonstrated

how an author is postmodern by identifying the emptiness of the subject (1991, p. 133). In their brief praise of

postmodernism, Best and Kellner recognize subjectivity as one of the needs

that postmodernism addresses (Kellner & Best, 1991,

p.286).

One of the problems I discuss in the prologue to this dissertation

is germane to the overall postmodern debate. The problem involves

how one comes to know the identity of a person. While this is not

the only issue, it is pivotal to the development of this dissertation.

I am only scratching the surface of the historical debate on this topic.

The debate continues without an apparent end in sight. In Chapter 3, I elaborate on the specific debates between

Habermas and Gadamer, and Habermas and Luhmann.

Postmodernism strives not to restrict interpretive possibilities.

Best’s and Kellner’s (1991) criticisms of postmodern

theory fall into three categories. They stated that "postmodern theory thus

lacks positive notions of the social, failing to provide normative accounts

of intersubjectivity, community, or solidarity" (Jameson,

1991, p. 283). Shortcomings include the inadequate handling

of the subject. The subject or agency problem leads to nihilism.

The postmodernists lack a grasp of and response to the real world.

Included in the postmodern debate are Habermas, Gadamer, and Luhmann.

In the opinion of Best and Kellner, Habermas fulfilled the expectations of

the postmodern agenda. Habermas provided a normative theory of intersubjectivity

by grounding his communication theory in an ego-alter relationship (self-others).

The recognition of the subject, or the problem of subjectivism as a

preoccupation of Western thought, is not new. Hans-Georg Gadamer (1976) joined Heidegger in attacking the Western obsession

with subjectivism. Gadamer’s objection primarily focuses on the subjective

approach that ignores the intrinsic temporality of human beings and the temporal

quality of interpretation. The problem Luhmann identified is the

postmodern tendency to fuse both the concepts of "Being" and knowledge of

self. He thought that this tendency obscures the dynamic quality of

the subject.

Luhmann concluded that, after society has reflected upon itself, the

"citizen of the world" reaches limits and the response is postmodernism

(1994a pp. 30-32). There is only so

much that came be said about any problem before the usefulness of the subject

is exhausted. Postmodernism’s reaction against anything "modern" understood

the alienation of the individual, attempted to address the problem of the

subject, and looked for solutions to problem of emancipation.

Luhmann recognized modern philosophy's need for a reinvigorated concept

of the subject, and his theory of differences or differentiation is that

attempt. He spoke about a rebellion against the search for universals

in which his systems theory of self-reference is a substitute for completeness

(1986d). Self-reference "designates every operation that refers to

something beyond itself and through this back to itself" (Luhmann, 1986a, p. 145).

For Luhmann, a social system of self-reference perceives the object

of its inquiry from the perspective of its own self- reference (Luhmann, 1986d). Therefore, the following

quote plays a pivotal role in my pursuit of an illustration of the differentiation

definition: "Self-reference is a necessary theoretical tool for system analysis:

in fact, without self-reference no system could be related to the environment"

(Luhmann, 1986d, p. 130).

The demonstration of the use of this theoretical tool requires a connection

between systems and self-reference. A demonstration of this linkage

answers Luhmann's question:

How, then, does society observe and describe the world by using itself as

a system-reference, by developing the higher reflection capacities of a system,

and by using the distinction of system and environment (of words and things)

to dissolve the paradox of the world as a frameless, indistinguishable totality

that cannot be observed? (Luhmann, 1993, pp. 774-775).

When this question is rephrased as a statement, the concept of self-reference

becomes an operable theoretical tool. The statement, "society observe[s]

and describe[s] the world by using itself as a system-reference," (1993, p. 774) is at the core of Luhmann’s reasoning.

My first task is to construct the presuppositions for "developing the

higher reflection capacities of a system" (p. 775). My second

task is to demonstrate theoretically the functioning of differentiation

"by using the distinction of system and environment to dissolve the paradox

of the world as a frameless, indistinguishable totality that cannot be observed"

(p. 775).

Branko Horvat (1982) described the climate in

which the postmodernist approaches social and economic issues. The

historical relevance of Horvat's "production of information" (1982, pp. 337-338) is pertinent to the advancement

of a system's reproductive advantage. The coordination necessary for

the operation of an information regulatory mechanism requires "organized

information diffusion" and an "enormously increased speed and precision of

information gathering and processing" (Horvat, 1982, pp.

336-338). David Prychitko went beyond this historical description

of the information age to address "the knowledge problem" of social planning

(1991, p. 87). The conscious allocation

of scarce resources is complicated by the multiple demands for a commodity.

The destination for a scarce commodity is decided on the basis of information

received.

The following summary illustrates the knowledge problem: "The assumption

of complete knowledge of the relevant factor, production functions, and

equilibrium prices does not solve the knowledge problem, but in fact obscures

it" (Prychitko, 1991, p. 88). A system

based on the concept of equilibrium faces the knowledge problem (pp. 87-88) because it ignores the problems

of the transmission of that knowledge. The amount of information available

today is unmatched in any prior century. The means to store and manipulate

it have never been more accessible and technologically advanced. Making that

knowledge useful is the challenge. One solution is to describe informational

advantages and organize information diffusion. This involves overcoming

the strictures of a theoretical language dependent on traditional definitions

where concepts are often equated with structure.

My argument is that, in the postmodern world, social systems need to

intensify efficient information advantages in order to maintain a viable

position. Luhmann's system of self-reference is the theoretical tool

needed to meet the needs of the postmodern world. It is a simple, direct,

and profound guide to effective information utilization.

Viewing the economy as a social system allows Horvat’s regulatory types

to be applied to the issues pertinent to the information age.

Study of the type of market operating under organized information diffusion

is especially relevant to the present postmodern discussion. As discussed

previously, the information age requires assessments of the validity and

usefulness of the superabundance of information. It is a knowledge

problem because the information is not being utilized.

The work of Talcott Parsons influenced both Habermas and Luhmann.

Parsons' theoretical insight is fundamental to both sociologists, each theoretician

gleaning ideas for divergent purposes. Luhmann stated that his intent

is not to reinvent social theory but rather to reinterpret and replace outdated

approaches to the examination of society (Luhmann,

1986c, p. 3, 1982). A recurring theme in Habermas' work

is the dualism concept of moral (subjective) and instrumental (objective)

action (Habermas, 1990).

Best and Kellner saw Habermas as providing solutions in areas where

the "extreme postmodernists" failed: "Habermas, by contrast, grounds his

communication theory in an ego-alter relation that privileges non-coercive

forms of inter-subjectivity" (Kellner & Best, 1991,

p. 283). The physical boundaries of an organism and the physiological

processes are easily discernible for Habermas, but not in reference to a

social entity. The difficulty in transforming this model into a social

systems approach comes from the way knowledge is built in support of theory.

Luhmann utilized the autopoietic system (self-producing) concept that

has its origins in the biological model (Maturana, 1981). "A social

system comes into being whenever an autopoietic connection of communications

occurs and distinguishes itself against an environment by restricting the

appropriate communications. Accordingly, social systems are not comprised

of persons and actions but of communications" (Luhmann, 1986a, p. 145). As

we shall see, Habermas reached an impasse at the juncture where he incorporated

hermeneutics into communicative action. Luhmann proceeded to build a

systems approach to differentiation.

Pivotal to Habermas' theory of communicative action is the interactive

established paradigm of intersubjective understanding (Habermas, 1984). Luhmann found it difficult

to comprehend how Habermas' complex theory of society can arise from everyday

discourse to form intersubjective understanding (Luhmann,

1986c). According to Luhmann, Habermas does not utilize the theoretical

resources available from other disciplines, for example, cybernetics and systems

theory. Rather, Habermas relies on a paradigm of intersubjective understanding

for his theoretical development.

Habermas attempted to use an interpretive approach in which intersubjectivity

reinvigorates critical theory. That is, he combined language, interaction,

and communication to restore the emancipatory intentions of critical theory

(Mendelson, 1979). Intersubjectivity,

to Habermas, is a level of communication, "on which the speaker and hearer,

through illocutionary acts, brings about the interpersonal relationships that

will allow them to achieve mutual understanding" (Habermas,

1976, p. 157). The distinction Habermas made between life-world

(web of relations) and system is similar to his insistence on the separation

between the object and subject of interpretation (Habermas,

1987; Hartmann, 1985).

In an article revisiting the debate between Habermas and Luhmann, Eva

Knodt concluded that Habermas' communicative action theory is a system in

a Luhmannian sense (Knodt, 1994, p. 79).

Knodt's argument that Habermas' "discourse" is the result of the closure

of a system draws from Luhmann's concept of functional differentiation (Luhmann, 1987). Discourse, for Habermas,

refers to a "linguistically mediated interaction" (Habermas,

1990, p. 201) that provides the testing grounds for validating universal

claims (Habermas, 1984, p. 42). Knodt's

analysis of Habermas conceptualizes discourse as an autopoietic (self-producing)

system that combines language, interaction, and communication. Knodt

was saying that Habermas' theory of communicative action is not a universal

social theory but can be included as one of the autopoietic systems within

Luhmann's systems approach. Habermas set up his theory of communicative

action within a set of boundaries that separate systems from the life world.

Since Luhmann viewed the world as a progressive sequence of interlinking systems,

Habermas’ communicative action theory becomes identified as one of those

many systems. Habermas separated systems from the life world, while

Luhmann saw all of life through systems. Luhmann’s definition of a

system does not distinguish between a system and the life-world as Habermas

argued. A system, for Luhmann, is all-encompassing and includes society

as one of many systems (Luhmann, 1987).

Habermas is a creative gleaner of diverse theoretical concepts who skillfully

integrated material useful for the development of his communicative action

theory (How, 1985). The concept of "creative misreading"

(How, 1985; Canovan, 1983;

La Capra, 1977) is applicable in these instances.

The creative misreading tailors another person's concepts for purposes not

necessarily consistent with the originator's intent, and it also creates obstacles

to one's own theoretical argument. I return to the discussion of creative misreadings in the chapter 5 of this dissertation.

One of Habermas' barriers is his inability to accept Luhmann's ideas

on system borders. This barrier prevents him from understanding

Luhmann's distinction between environment and system. The parameters

by which a system functions or defines its activity are termed its "borders."

For example, the borders of an organizational system are fixed, thus defining

the scope and vision for the system. Family systems do not have fixed

borders.

In the late 1960s, a debate between Habermas and Luhmann focused on

their approaches to systems and society. In this forum, Habermas began

to publicly challenge Luhmann’s functional claims for a systems theory.

Apparently, Habermas saw Luhmann’s theory as unraveling the advances made

in Parsons’ action theory. Luhmann, on the other hand, considered

that his work takes Parsons’ formulations to the next level. He considered

that Parsons would have updated his thinking in response to new theoretical

breakthroughs.

Habermas engaged in another debate, this time with Gadamer, that shed

light on Luhmann’s position on the concept of subject. Ideology and

interpretation were the focal points for this encounter. Habermas

came out of the Frankfurt School for Social Research with an agenda to reinvigorate

the mandate for emancipation. Habermas’ solution was to introduce interpretation

as a method in the study of economic and political systems.

After examining Habermas’ evaluation of Gadamer’s hermeneutics (method

for interpreting), my conclusion is that Habermas’ rejection of Gadamer’s

ontological perspective is based on Habermas’ preservation of the distinction

between object and subject. Gadamer objected to Habermas’ acquisition of

hermeneutics for analysis in the social sciences because of the logic of

intentional alienation and distancing methods (Gadamer,

1976, pp. 26-36). Historically, sociology requires

a dogmatic objectivism. This objectivism stands in the way of a hermeneutical

method which is based on the concept of hermeneutical reflection (combining

history and self). Maintaining the distinction between subject and

object leads to problems.

Habermas used hermeneutics for the purpose of emancipation from the

shackles of tradition, veering from Gadamer’s starting point for interpretation.

Meaning defined through the concept of the subject, that is, through personal

reflection, becomes the object of thought. Gadamer (1976) believed that the origin of interpretation for

any experience comes before the action the experience initiates. For

Luhmann, this means that communication causes action and communicative action

is a function of the social system. Communication precedes action ,

contrary to Habermas’ theory in which action is a precursor to communication

through intersubjectivity. The logic of Luhmann’s conclusion is that

if the subject were "characterized by the conscious actualization of the

intentional structures of experience" (1990a, p.

22), it is then placed outside of "Being" (Sein, ekstasis).

"It gives us something that cannot be: an isolated ego" (Luhmann, 1990a, p. 22).

The problems faced when accessing an overwhelming amount of information

create the need for theoretical perspectives radically different from those

that may have been sufficient in past history. If the distinction between

the objective and the subjective is removed from the sociological method,

then the discipline is in danger of losing its scientific perspective.

If the distinction remains, then the fears of the postmodernists that the

individual has lost his unique identity and is in need of emancipation are

justified.

Luhmann’s solution includes the exploration of the theory of differentiation,

especially the distinction made between system and environment (1982, p. 230). The approach

removes us from the quagmire of individual roles and activities and forces

us to examine the evolving process of describing differences. The goal includes

a need to determine the validity and usefulness of the superabundance of

information. Luhmann's systems theory connects us to the information

by giving control. Our understanding of who we are is far behind our

ability to utilize information.

Go to Table of Contents

CHAPTER THREE

THEORETICAL CONSIDERATION

WHEN EXAMINING NIKLAS LUHMANN'S THEORY OF DIFFERENTIATION

The first part of this section will explore the background and development

for Luhmann's subject-free concept. The subject-free concept of action

must be understood before any illustration of differentiation. Double

contingency, interpenetration, and self-reference are constructs for the

subject-free concept. Language restricts our ability to conceive of

a subject-free thought process. Luhmann stated that the reason for

this difficulty is that:

The predication is forced on the subject of sentences; this suggests the

idea, and reinforces the old habit of thinking, that we deal with 'things,'

to which any qualities, relations, activities, or surprises must be ascribed

.... In this form, things provide handy clues for managing references to

the world. (1995/1984, p. 77).

It is not always evident how double contingency, interpenetration, and

self-reference relate to each other. The difficulty with following

Luhmann's development of these ideas is that he has reconstructed each concept

so it is hardly recognized as it was originally formulated. Luhmann's

development of double contingency, interpenetration, and self-reference is

nontraditional.

The second part develops the rationale for the functioning of system

and environment in Luhmann's scheme. I also discuss and identify three

essential features in the theory of differentiation: a) The interdependence

of variables maintains system, b) the environment allows for structures

and processes, and c) a social system emerges as a result of communication

through an autopoietic connection.

Background and Development for the Subject-Free Concept

Taking into account the complexities of modern society, Luhmann advanced

beyond action theory. Responding to the need for a current social

theory that addresses the concerns of an increasingly complex society, Luhmann

(1982) split away from the structural-functionalism

of his mentor, Talcott Parsons. For Luhmann, the function of social

analysis no longer refers to the activity of roles or participants in activities

but rather to the relationship between system and environment (Luhmann, 1995, p. 176).

In challenging Parsons' (1977) functional

structure of social systems, Luhmann broke away from the old Kantian notion

of the subject (Luhmann, 1982).

Luhmann stated that the term "subject" belongs to the historical tradition

which ties the subject to the foundation of modern reflexive (turning in

on oneself) individualism (personal communication,

September 20, 1996). This historical tradition stems from the philosophical

works on self-identity (Kant, 1965). An argument

exists for a Kantian transcendental self where the self does not acqire self-knowledge

through self-awareness (Kitcher, 1982). Parsons’

social image of man views the individual as social process of interaction

between the self as subject and the self as object.

Luhmann's approach severed the connection between the physical world

and the social to describe and analyze problems relevant to the information

age. A Luhmannian approach dismisses any type of equilibrium notion

in systems. The result of Luhmann's rejection of equilibrium theories

was the discarding of input-output social models, especially Parsons' four-function

social system theory (Luhmann, 1982,

pp. 52-55; 1986a, p. 6; 1990b, p. 93). Luhmann did not totally

disregard the applicability of input-output social models. In recent

correspondence, Luhmann reiterated the restrictive characteristics of the

input-output schema and saw the illustration for these restrictions in the

firm (organization) which distinguishes between labor markets and product

markets (personal communication,

September, 20, 1996).

A systems approach that starts with communication replaces Parsons'

"action theory" that emanated from the interaction of actors. The

following quote emphasizes Luhmann's use of communication rather than action

as the basis of social analysis: "Sociality is not a special case of action;

instead, action is constituted in social systems by means of communication

and attribution as a reduction of complexity, as an indispensable self-simplification

of the system" (Luhmann, 1995, p. 137).

The discussion of the postmodernist debate earlier emphasized the need

for more self-defining philosophy. Postmodernists felt that modernism

alienated the individual. There was a call for a return to the subject

of self-knowledge. Luhmann denied the traditional approach to self-knowledge

which presupposes an actor in the sense of subject. The subject-free

approach begins with the system’s necessity to observe itself only from

what it can observe (Luhmann, 1991).

In analyzing the observation of self-reproducing systems, Luhmann noted

that part of the problem is that the observer is also a self-reproducing

system. Thus, it finds itself constrained by the conditions of its own self-reproduction,

and it includes itself in the field of operations, because it cannot avoid

gaining information about itself (Luhmann,

1986b, p. 186). This observation of observation allows us

to view the blind spots in others and excludes the possibility for self-observation.

We know ourselves only through others’ observation of our blind spots. Our

connection with the world is through Luhmann’s insistence on the fundamental

blindness of all observations. This connection is liberating and does

not separate or alienate us from our world. The implication for the type of

connection Luhmann proposed involves rethinking the way in which we know ourselves.

Luhmann not only challenged the subject, he illuminated it. Our blind

spots connect us to what is real. Knowledge of ourselves is thus subject-free.

The construction of a subject-free way of theorizing begins with Luhmann’s

incorporation of the biological theory of autopoiesis (Maturana, 1981).

Autopoiesis defines systems that distinguish between the system’s internal

environment and the environment’s external realm. The system’s self-perpetuation

depends upon the physical operation of the system. Luhmann adapted

the autopoietic terminology to include psychic and social systems by defining

these systems as nonliving. These nonliving systems reproduce themselves

through their closure and openness. Closure is the inability of people

to understand themselves outside the context of a social system. The

psychic system reproduces itself through its consciousness, while the social

system propagates through communication. Openness characterizes the structural

nature of the system and environment.

Luhmann’s idea of closure means that communication happens within the

system and not between the system and environment. Communication is

always an internal operation of the system. The notion of openness

allows the system to expand and shrink according to the requirements of the

social system. Luhmann extended the biological autopoietic model by

distinguishing between the social system’s operation and its observation.

The act of observing is discussed later as interpenetration.

The distinction between the system’s self-perpetuation and the act of distinguishing

between system and environment results in the creation of information.

The differentiation function of a system includes itself in the field of

operations and, as a result, the system cannot avoid gaining information

about itself.

Self-reference emphasizes the process of differentiating the differences

between the system and the environment. This act of identifying differences

illustrates the elemental psychological attribute of distinguishing figure

from ground. Philosophically, this distinguishing feature creates

a tautology or paradox. This means that the problem of paradox presents

an impasse to the practical application of knowing something. The

paradox, from a philosophical perspective, means that a distinction is made

between what something "is" and what it "is not." The patient

states that he is "ill" and the observer (the physician) knows the patient

is ill by distinguishing between what is said by the patient and what is

not. Ill is figure and what is not ill is ground. The distinction

between the patient’s statement, ill, and the possibility that he would not

have stated it creates the paradox.

Luhmann’s solution to this problem of knowing, paradox, is fully discussed

in the subsection, "Double Contingency." The current discussion focuses

on what the solution provides. I will illustrate how I have incorporated

illness into Luhmann’s frame of reference. In order to accomplish this,

I need to explain a few concepts basic to Luhmann’s vocabulary.

Code, communication, program, and information are conceptual elements that

have a common thread. These terms associate with each other in a very

dependent manner. The speech uttered by a person is contingent upon

an outcome made possible by a potential choice. Information is dormant

until it becomes part of the communicative function of a system. Information,

seen as an event rather than a commodity, serves the goals and interests of

the particular system. The defining characteristic of code is the program.

Any evidence of communication indicates the existence of a paradox.

Luhmann’s systems theory answers the paradoxical question by providing the

means to distinguish between what something "is" and what it "is not."

The following illustration addresses this point. In a coastal setting,

in order to get to the beach by the shortest route, the public walks across

private property repeatedly. After a certain length of time and volume

of use, the well-worn beach access becomes part of public domain. In this

illustration, code is the choice the public makes to access the beach.

The code is contingent on the possibility of other routes or choices.

The system, in this case, is the public reaching a destination. The

program is the conditions that allow this choice of route to become the

rule or criteria for the path to become a public right-of-way. Information

is the event that occurs when an observer sees the people use the well-worn

path. Communication is the synthesis of three elements: the information

plus the person’s decision based on the contingency to do otherwise, and

the understanding resulting from the decision to take this route.

Luhmann continued to address questions posed by the dilemma of paradox

through an application of second-order cybernetics. Cybernetics (from

the Greek word for helmsman) defines the relationship between the observing

system and the observer. Second-order cybernetics includes the observer

in the system studied while first-order cybernetics is simply a system of

observation (von Foerster, 1970). The

relationship, one of inclusion with the system of observation, affords the

observer insight. The insight gained by a person is not accessed

through personal self-awareness but by the social system undoing the self-referential

paradox. The desire to avoid the confusion between action and its presupposed

actor requires the conscious effort to view both action and actor as constructs

of the observer. Therefore, any reference to self must be seen as the

observer’s invention. This also presupposes that there is no value in

serching for universals but, rather, completeness in understanding how paradoxes

define differences, the heart of the reproductive cycle of systems.

Self-reference "designates every operation that refers to something beyond

itself and through this back to itself" (Luhmann, 1986a, p. 145).

The patient and physician continue their dialogue and, as their encounter

progresses, the observation of the blind spots in each other contributes

to the knowledge gained. Chapter 4 describes illness as a theme

developed during a clinical encounter.

The attempt to access knowledge of what "is" or "is not," creates the

paradox. There are two solutions to this problem. The first

solution is to ignore the problem altogether and develop theories excluding

this paradox. The second, the solution proposed by Luhmann, is

the binary coding concept. Binary codes arise out of positive and negative

values assigned to what "is" or "is not" thus allowing for the possibility

that one choice could transform into the other contingent choice. This,

therefore, allows systems through binary codes to "undo" paradox. This

undoing process occurs as the system orients itself to the difference between

figure and ground. The system adjusts to what "is" or "is not" through

its own self-reference.

The analysis of social systems requires identifiable components -- these

components, for Luhmann, are utterances. The action of the speaker

is known through the sequential unfolding of utterances. The unfolding

of utterances creates the need for events to be coded or uncoded. During

this process of the sequential unfolding of utterances, one assumes coding.

The rationale for this assumption is that an utterance presupposes the

choice made: 1) to maintain current usage and provide opportunity to reformulate

it appropriately within the experience and 2) provide information that verifies

the choice to exclude other usages and meanings. In order to trace

the unfolding of this process, binary codes identify the duplication of information

created by the paradox.

As stated earlier, cybernetics defines the relationship between the

observing system and the observer, while second-order cybernetics includes

the observer in the system studied. The relationship between observation

and system, paired with Luhmann’s insistance on action being an invention

of the observer and following the communication process of social systems,

creates the paradox. The foundation for the paradox is the contingency

that "other" choices were possible and are still options for the unfolding

of the utterances (events).

Adjusting to the paradox can only be accomplished by the observation of

another observing system. The presence and recognition of the paradox

provides building blocks for "knowing," thus eliminating the need for presuppositions,

a requirement for our first solution.

Double Contingency

Luhmann furthered Parsons' functional approach by confronting problems

about the transmission of knowledge. Luhmann was able to build upon

the work of Parsons and make it relevant to the complexities of today's

world.

In seeking solutions to problems encountered when explaining the transmission

of knowledge, Parsons found that double contingency was an obstacle (Parsons, 1951). Double contingency involves

the relationship between the speaker and the addressee. Simply put,

the difficulty is that action cannot take place when the speaker is waiting

for the addressee to respond, and the addressee's response is dependent upon

the speaker’s action. This creates a communication stand-off, each participant

waiting for the other.

Parsons' solution, articulated in his concept of action, makes the assumption

that the participants interact based on preexisting norms. Luhmann

recognized the problem of double contingency; however, he maintained that

Parsons

avoided the problem, sidestepping it with the notion of normative assumptions.

The problems Luhmann encountered are no longer structural ones involving

intersubjectivity (or between "actors") but have to do with the function

of communication. He used the problem of double contingency as a solution

to overcome the obstacle it creates. Rather than focus on the impasse

created by the double contingency, Luhmann took the process back to the creation

and reproduction of meaning. At this point, Luhmann attempts to solve

these functional problems by appealing to the success of models from biology

(Maturana, 1981; von Bertalanffy, 1950). The across-the-board transfer

of biological theory to social theory presents problems. Luhmann resolved

the difficulties by reconceptualizing the social as nonliving systems "whose

basic elements consist of communications, vanishing events in time that, in

producing the networks that produce them, constitute emergent orders of temporalized

complexity" (Knodt, 1995, p. xxiii).

There is a gap between what is understood by the speaker and what is

understood by the addressee. For Luhmann, this gap is the contingency

which allows for affirmation or negation of the exchange between participants.

The contingency is reduced as the communication initiates action, thus determining

an affirmation or negation of the essence of the other participant.

From this perspective action is an emergent phenomenon. This

returns to the prior discussion concerning the blind spots that we all share.

We are able to see the blind spots of others while oblivious to our own; therefore,

the gap between speaker and addressee.

Interpersonal Interpenetration

The formation of social relationships occurs through personal and impersonal

contacts. The process of interpenetration allows recognition of the

personal characteristics that form social relationships. Knowledge

of human beings (psychic systems) requires a key to understanding the relationship

between human beings and social systems. The key is the concept of

interpenetration. Interpenetration requires a reciprocal relationship

between autopoietic systems as they become part of the environment for each

other. The psychic system (consciousness) is part of the environment of the

social system. The reciprocal interdependence creates disorder for

the psychic system.

Both psychic systems and social systems are autopoietic, which means

that they share a structural relationship. Due to the fact that

psychic systems and social systems exist completely dependently on each other,

further explanation is required. The mind, through the psychic system,

is sustained through the state of consciousness, while social systems continue

their existence with communication. It is in this state of necessity

that these different systems (psychic and social) form a relationship

where this need for a reciprocal interdependency creates the disorder.

The cause for the disorder within the psychic system (one’s consciousness

awareness) is interpenetration. Language is the evolutionary result

of an accomplishment of the interpenetration process. The disorder

present in the psychic system is the effect of language transferring social

complexity into psychic complexity.

Social systems emerge as the result of the tumultuous effort psychic

systems expend in the effort to communicate.

The mind therefore participates in communication as a structurally determined

system and as a medium. This is only possible because the mind and communication,

psychic systems, and social systems, never fuse or even partially overlap,

but are completely separate, self-referentially closed, autopoietic- reproductive

systems. As I said: humans cannot communicate. (Luhmann, 1994b, p. 379)

The accomplishment of this evolutionary process of interpenetration

is language (Luhmann, 1995/1984).

Self-Reference

The transcendental distinction between subject and object was replaced

by the distinction between system and environment. I will now continue

the discussion about the development of the relationships between social

system and elements (includes psychic systems) of the environment.

Originally, my discussion introduced Luhmann’s concept of interpersonal interpenetration

by way of their (system and environment) reciprocal interdependence creating

disorder for the psychic system. I emphasized that, as a result of the

accomplishments of interpenetration, language transferred social complexity

into psychic complexity.

Although complexity cannot be observed, the consequence of its presence

is felt in the tension between the system (self-reference) and environment

(everything else that is not system). Continuing the development,

Luhmann shifted his analysis to redefining the system/environment distinction

within a general theory of self-referential systems (1995/1984). Luhmann replaced the subject/ object

relationship with the self-referential system where communication is the

lowest common denominator for social analysis. For Luhmann, the self

only exists because of the difference exhibited between itself and everything

else.

Problems of how one conducts empirical research arise with self-referential

systems theory. This problem is fully discussed in chapter 5, "Creative

Misreadings." The theoretical consideration important for the present

discussion is how a self-referential system can replace the traditional

concept of the subject. In his appeal to let go of the subject, Luhmann

summarized our attachment: "The significance of the figure of 'the subject'

(in the singular) was that it offered a basis for all knowledge and all action

without making itself dependent on an analysis of society" (1991, p. xli). The use of terms such as "subjectivity"

and "subject" are useful only when discussing comparisons and contrasts between

structuralists and functionalists. If one continues to push for a subject/object

comparison, then the subject refers to self-reference and object fulfills

Luhmann's notion of environment. The subject can only have some comparative

value if defined in dynamic terms, such as: "It lays the foundations for

itself and everything else" (Luhmann, 1991, xxxix).

It is my contention that American theorists would understand Luhmann's

theory if they could set aside the subject/object format. Robert Bales

and James Coleman are two American theorists who rely on the subject/object

dichotomy in their theoretical development. Bales (1950,

pp. 71-72) made reference to the subject-object polarity as an important

aspect in stabilizing the relationship between people. Coleman (1990, p. 507), focusing on the actor's role in

society, used the concept of the object self and the acting self.

Bales treated generalizations made in relation to personality, social

system, and culture as structures removed from each other through increased

increments of abstraction (1950, p. 31, Bales & Cohen, 1979). Bales ties these

levels of observation to the subject-object polarity: "The concepts in that

section [actor & situation as a frame of reference, see pp. 42-48]

are all derived from the subject-object polarity which we assume to be a descriptive

characteristic of any human interaction" (1950, p. 49).

Warning against traps in social theory, Coleman (1990,

1988) attempts to bridge the gap between an extreme emphasis on subjectivity

and an obsession with objectivity. The first trap is radical methodological

individualism; this concept explains social action as the aggregate of individual

actions. The second trap is structuralism which does away with the concept

of subject or human agency.

One of the effects of structuralism, argued Coleman, is a concentration

on the whole structural aspect of social interaction. This argument claims

that structuralism eclipses individual choice and, therefore, excludes human

freedom. In order to avoid the theoretical traps against which Coleman

warned, theorists must walk a tightrope between radical individualism and

extreme structuralism.

Focus, in Luhmann’s theory, is on social systems. When the concept

of self-reference is viewed from his perspective, terminology points to

the function of social systems and not to personal or individual activities

of people. Self-reference is a reference to a function of the social

system, and it "designates every operation that refers to something beyond

itself and through this back to itself" (Luhmann, 1986a, p. 144).

Luhmann hesitated to call the actor a subject, since this presupposes

that an actor creates action. The argument continues as the subject

historically connotes a self-founding. Action, for Luhmann, follows

communication and, therefore, cannot be the creation of what historically

is the subject, that is, the individual. Action is the result of a

social system rather than the psychic system. For this reason, the focus

of Luhmann’s work is self-reference rather than what has been the traditional

starting point, the self.

An illustration of the difference between Luhmann and the "structuralists"

could be envisioned as follows: Consider the content of social analysis

as if two people in a park were playing ball. If one took a photograph

of that scene, the structuralists could analyze the figures in the photo

as subject and object. Luhmann would see nothing from a photograph.

Understanding, for Luhmann, comes from observing the motion inherent in

the activity.

The cartoon depicting two theorists at a local sports bar (Fig. 1) illustrates a principle of differentiation.

This principle is a process by which people distinguish between figure and

ground. The first depiction of a TV screen represents a frozen segment of

time, a still image of an occurrence in the game. Although Luhmann saw

nothing on the screen, Habermas drew upon interpretation for analysis and

conclusion. The instant replay broadcast in the last section of the

panel graphically illustrates Luhmann’s process by which the distinction

between environment and system is made. The environment in the

illustration is the baseball diamond. The social system under analysis

is the game of baseball in which the players move according to the parameters

of the game (system). This dynamic event can be seen and understood

by Luhmann, whereas the static "photo image" representation showed him nothing.

Understanding, as illustrated in the cartoon metaphor, does not require

interpretation.

Go to Table of Contents

System and Environment

Elemental Constructs

The concepts of system and environment are so central to Luhmann's

theory that, without these words, the theory of differentiation would be

hard to describe. Luhmann's development of systems and environment

is through the relationship these concepts have with each other. The

existence of system and environment can only be observed through their difference.

This observation is through the effects of the communication. Communication

is the basis for system reproduction and operation (Luhmann, 1986a). The identifiable

components of the system are utterances for social systems. The

utterances, when followed sequentially, represent the action of the speaker.

Utterances are the building blocks for the system's regeneration (Luhmann, 1990a, p. 12).

The activity of speech (utterances) is the identifiable element in illustrating

the theory of differentiation. It is important to understand

that the activities of speech (utterances) are identifiable events and not

the abstraction of a physical element. Simply stated, differentiation

is the act of distinguishing between events. The smallest essential

event is a potentially negatable event (Luhmann, 1995/1984,

p. 154). The negatable event (utterance), as we will see in what

follows, allows the system to have a point of reference.

In a subject-free context, physical representations are replaced with

events unfolding during a sequence of occurances over a period of time.

Luhmann differed from Parsons in that "social systems are not comprised

of persons and actions but of communications" (Luhmann, 1986a, p. 145). The analysis,

in this case, does not examine the parts of speech or the speaker. Physical

representations of the activity and abstract representations of human beings

(speaker) are avoided. The basic element of analysis is the "event."

For example, a conference consists of a series of events and activities that

define its purpose. The events have the potential for being useful

or not in accomplishing the goal of the conference. This potential

or possibility that the individual events could or could not contribute,

is the essence of what Luhmann called the negatable event.

The system reference determines the point of view from which one begins

an observation and designates the system's boundaries. This point

of reference is arbitrary and determined by the observer who defines the

parameters of the system. The reference point starts the process toward

a reduction in complexity. Luhmann stated that "the choice of a system

reference only determines the system from whose point of view everything

else is environment" (1990b, p. 418).

A system produces information through a comparison process with other possibilities;

information is not something "out there" waiting for absorption (Luhmann, 1990a, p. 4).

Essential Features

During the course of tracking the development of Luhmann's ideas

on systems, I observed three distinct emphases:

(1) the interdependence of variables maintains systems,

(2) the environment allows for structures/processes, and

(3) a social system emerges as a result of communication

through an autopoietic connection.

Luhmann's thinking about social systems began with Parsons' ideas of interaction

as a process of systems. The idea that the fundamental property of

a system is the interdependence of variables provided the basis for Luhmann's

approach to systems. The interdependence describes the relationship

between elements of a system. The following quote marks the beginning

of Luhmann’s thinking on the interdependency of variables in a system:

"The boundary of the system is defined in terms of ‘constancy patterns’

that are tied up to a harmonious set of common norms and values, mutually

supporting expectations, and the like" (Parsons &

Shils, 1952, p. 107). Parsons' description gave structure to the

concept of system.

A system is a set of constructs arranged in a fashion that links elements

serving a unified function. With the structure in place, Luhmann advanced

upon Parsons' approach with a concentration on the "unifying function" of

system. He considered that Parsons would have updated his thinking

in response to new theoretical breakthroughs rather than using outdated approaches

to the examination of society.

The process orientation requires the synthesis of information, utterance,

and understanding in order to generate meaning through the process of communication

(Luhmann, 1990a, p. 3; 1979, p. xi). This process

is a basic requirement of the system of Luhmann's approach. The environment

is the requirement of Luhmann's theory that makes it possible for the structures

and processes of a system to interact.

This is the case since only by reference to an environment is it possible

to distinguish (in any given system) between what functions as an element

and what functions as a relation between elements. Exaggerating slightly,